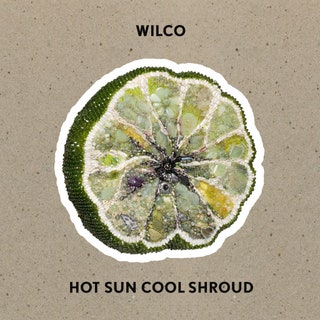

On their first new album in six years, the folk troubadours balance out-of-time balladry with a mature sensibility that’s attuned to melancholy and mortality in the present.

Once a figure of ridicule and derision, the nerd defined the first decades of the 21st century even more than the hipster or the bro. This seemed like a promising development, before it soured into misogynistic gaming culture and The Big Bang Theory. The Decemberists, named after an obscure Russian revolution (which they winkingly misspelled), represented a more benevolent side of geekdom: They were smart, of course, but also very passionate about arcana. They fussed over prog-folk epics, sea shanties, and Shirley Collins the way other nerds nitpicked D&D campaigns or Star Wars canon. We knew the terrain of frontman Colin Meloy’s inner emotional life not through confessional lyrics but through his obsessions.

The Decemberists weren’t rock nerds, though, which may be why actual rock nerds dismissed them in their heyday. Instead, they were theater nerds—a wildly intense phylum of geek. Meloy wrote songs like playlets, constantly implying a proscenium, and the band performed them like a troupe of thespians, occasionally even reenacting Tolkien battles onstage. There was an element of playacting in every song, which made them seem like the nerdiest band around (even Barenaked Ladies’ theme songs never went that deep). That dramaturgical proclivity festooned quote marks around certain songs (“The Mariner’s Revenge Song”) and even entire albums (The Hazards of Love), but their music always seemed to spring from a benign fixation with the historic and the folkloric.

With their ninth studio album, the Decemberists have done something that few 21st-century nerds even consider: They’ve matured in their relationship with their obsessions. They’ve grown up. Not a lot, but enough. The archaic syntax of the title As It Ever Was, So It Will Be Again suggests a “return to form” or at the very least a career retrospective. But the album is nothing quite so lofty: The Decemberists are dressing up in yesteryear’s costumery—the character-driven songs of Picaresque, the jangle rock of The King Is Dead, the shaky political engagement of I’ll Be Your Girl—but there are no quote marks around these songs. It’s more a personal reckoning with their own past: a rummage sale of dusty enthusiasms.

So there’s an unexpected melancholy to these new story-songs, a poignancy that wouldn’t have been possible 15 or 20 years ago. Meloy understands we obsess differently in our dotage, with a new sense of impermanence and a more acute understanding of mortality. He has sung about death many times before, but it sounds a little more immediate on opener “Burial Ground.” There’s an easy charm in Meloy’s gashlycrumb wit and in the band’s ability to combine various influences so that the familiar—’60s folk melodies and pop arrangements—sounds slightly unplaceable. Is it more Beach Boys outtake or more pre-Days of Future Passed Moody Blues? “Burial Ground” operates not unlike Fairport Convention’s “Come All Ye”: It’s an invocation, an invitation to the graveyard, and the Decemberists know we’re all headed in that direction anyway.

That’s how they start the album, and every song that follows—from the “Hell”-acious “Oh No!” to the bittersweet love song “All I Want Is You”—ponders the inevitable end of every story. The long white veil in “Long White Veil” hides not a bride’s face but a corpse’s frozen countenance (gesturing toward the Lefty Frizzell hit “The Long Black Veil”), and “Don’t Go to the Woods” is nothing but dread and caution: a preamble to “The Black Maria,” the dark heart of this album. That title might refer to arcane slang for a paddy wagon, or it might be the Beasts Pirates in One Piece, but Meloy is writing his own canon here. Death is a walking shadow, never glimpsed by the living but known by its heavy footfalls in the hallway. “Turn out your lantern light, set your affairs to right,” Meloy sings over a strummed acoustic guitar and a lone funereal horn. “The Black Maria comes for us all.”

As fanciful as these songs can be, the Decemberists can’t help but ground them in the very real, very horrifying present. That’s never been their strongest subject, but they at least try to meet our current moment with the capitalist allegory of “The Reapers” and even “William Fitzwilliam” (which is haunted by the ghost of John Prine’s “Paradise”). The angriest song here, “America Made Me,” might be twice as powerful if it was half as clever, but there is something to be said for soundtracking dissent with jaunty piano and party horns. It’s a tack they’ve been deploying since “16 Military Wives,” although here the sentiment is more potent in its outrage and disgust.

As It Ever Was, So It Will Be Again ends as you might expect: with a nearly 20-minute epic called “Joan in the Garden.” Its winding length and multi-part structure gesture toward The Tain and its spawn The Hazards of Love, but it might align more closely with “I Was Meant for the Stage,” their creative exegesis from Her Majesty. It’s a song about what the Decemberists do and why they do it, a meditation on art as a weapon against death—but, in this case, not their own. Joan is literally in the garden, deep in the soil, but Meloy can resurrect her with words: “Make her 10 miles tall, make her arms cleave mountains… write a line, erase a line.” After a five-minute folk passage and a five-minute prog section, the Decemberists give over nearly 10 minutes more to ambient noises, stray rhythms, plunked strings, errant synths. It sounds like they’re striking the set and clearing the stage—a softer kind of death—and it’s weirdly moving. They might have stopped there rather than append a dramatic coda, but they never could resist a big finish. As it ever was.

.jpg)

.jpg)